Jamie Ewan trekked across Bleaklow Moor in Derbyshire’s High Peaks to visit the final resting place of a Boeing RB-29A Superfortress. But what happened on a fateful day in 1948?

No one will ever know what was going through the minds of the 11 crew and two passengers on board the United States Air Force (USAF) Boeing RB-29A Superfortress Over Exposed as it powered through the skies of Derbyshire on November 3, 1948. With a broken layer of dark cloud often hiding the unforgiving moorland-covered plateaus of the Peak District below them, one wonders if the crew were thinking of home. With their ‘temporary duty’ – or TDY – complete, after that flight they were just a few days away from returning Stateside to their family and friends. Unknown to them, they had taken off for the final time…

The road to Bleaklow

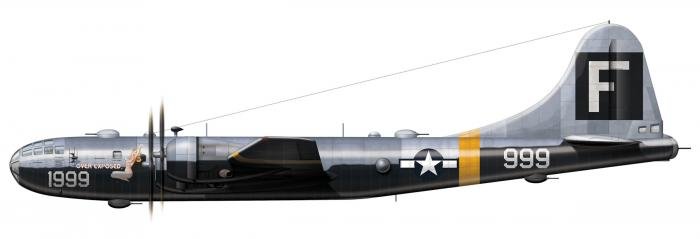

The Superfortress destined to become Over Exposed rolled out of Boeing’s Renton factory in Washington in late June 1945. Assigned the serial 44-61999, the airframe was built as part of an order for 99 examples of the four-engine heavy bomber bound for what was then the United States Army Air Force. It was the 89th B-29A-55-BN. Delivered the following month and prepared for war across the Southeast Asian theatre, the aircraft was soon considered surplus with the Japanese surrendering on September 2 that year. However, shortly after it was one of 118 B-29s chosen for conversion for photographic reconnaissance work. Redesignated an F-13A, the aircraft was fitted with one K-18, three K-17B and two K-22 cameras – all of which were developed by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation – while the type’s standard bombing equipment and defensive armament were retained.

Initially assigned to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Group’s (RG) 16th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron (PRS) at MacDill Field in Florida, the airframe was diverted to the 58th Bombardment Wing’s 509th Composite Group at Roswell Army Air Force Base in New Mexico in April 1946. On its arrival, the aircraft was quickly dispatched to Kwajalein Island in the North Pacific Ocean to support Operation Crossroads – the United States’ atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. Assigned to the group’s Tactical Operations Unit (dubbed Task Unit 1.5.2), 44-61999 was one of eight F-13s allocated to conduct aerial photographic operations and radiological reconnaissance missions during the testing.

As such, on July 1, the aeroplane accompanied B-29 44-27354 Dave’s Dream as it dropped a free-fall 23-kiloton yield Y-1561 ‘Fat Man’ Mark III atomic bomb nicknamed ‘Gilda’ under the codename ‘Test Able’. Armed with 25 cameras, 44-61999’s crew was tasked with capturing the weapon leaving 44-27354 before diving away. By the time the bomb exploded over the Bikini Atoll lagoon, F-13A 44-61999 was some seven miles away. On July 25, ’61999 was again in action supporting ‘Test Baker’ – this time capturing the detonation of a near identical weapon (dubbed ‘Helen of Bikini’) underwater.

With the story of 44-61999 being told the world over, it has been widely recounted that the aeroplane gained its now famous Over Exposed moniker while serving at Kwajalein for getting too close to a so-called ‘nuclear flash’ over Bikini Atoll. Shortly after Test Baker, the eight F-13s were flown back to the US where the extra cameras were removed at Wright Field in Ohio, before being delivered to Roswell for contamination checks. With these completed, 44-61999 was returned to the 16th PRS at MacDill in late 1947 and pressed into regular squadron service as a long-range photographic reconnaissance platform with Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) 55th RG.

From Bikini to Berlin

As the days of 1948 were ticked off the calendar, it became harder to ignore the menacing clouds of conflict building up on Europe’s horizon as cracks began to appear in the multinational occupation of post-war Germany.

The communist Soviet Union began to flex its muscles during the nascent days of the Cold War. The crisis in Germany intensified on June 24, when Soviet forces blockaded rail, road and water access to Allied-controlled areas. Isolating more than two million people and desperate to stave off all-out war, this left the western powers with only one viable option – airlifting supplies to Berlin until the crisis could be solved diplomatically. Two days later on June 26, what would become one of the biggest airlifts in history began. But how is it that Over Exposed, by then designated an RB-29A in line with the then newly established USAF, found itself flying through the skies of Europe?

In late July 1948, as part of US efforts to support the besieged city, which required around 4,500 tons of coal and food per day, USAF Chief of Staff Gen Hoyt Vandenberg ordered the deployment of some 90 Superfortresses to various bases across the UK. The aircraft – assigned to SAC’s 2nd Bombardment Wing – would augment the already struggling transport fleets and signal the West’s resolve to sustain the airlift as tensions continued. However, among the bombers the USAF quietly interposed some of its newly designated RB-29As to secretly ‘map’ Soviet-held territory using six cameras that could capture a strip of ground three miles wide per frame.

As such, the 16th PRS – then under the command of the 311th Air Division – quickly dispatched several of its machines (including 44-61999) on a TDY to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. While the exact number of ‘airlift’ flights over Berlin that Over Exposed conducted over the following two months is not known, it is known that the aeroplane was regularly flown by the same crew throughout its European detachment. These were the men who climbed into the skies on November 3 that year for what should have been a routine flight. Led by Capt Landon Peter Tanner (pilot), the rest of the crew comprised: Capt Harry Stroud (co-pilot); TSgt Ralph W Fields (engineer); Sgt Charles R Wilbanks (navigator); SSgt Gene A Gartner (radio operator); SSgt David D Moore (radar operator); camera crew TSgt Saul R Banks, Sgt Donald R Abrogast, Sgt Robert I Doyle and PFC William M Burrows; and Capt Howard E Keel (photographic advisor).

Fateful flight

Despite their rotation in England having come to an end, Tanner and his crew were scheduled to undertake one of the regular ‘runs’ to the USAF base at Burtonwood in Cheshire, as part of a three-ship on November 3, 1948.

What had once been the largest facility of its type in Europe was now being used as the primary maintenance base for Douglas C-54 Skymasters taking part in the Berlin Airlift. However, despite having had a significant US presence since 1942, supplies, mail and payroll packages bound for the so-called ‘little America of the northwest’ were initially delivered to Scampton. Similarly, those destined for the States were also sent via the Lincolnshire base. As a result, it wasn’t unusual to have multiple ‘Superforts’ crisscrossing the uplands of the Peak District each day.

On that fateful day, the crew of Over Exposed welcomed two passengers – Cpls Clarence M Franssen and George Ingram Jr. Routine flights like this didn’t require a full crew, but most of the ’29s were full as it gave those on board the opportunity to acquire some so-called ‘creature comforts’ found at the American base while so far from home. While the exact happenings aboard 44-61999 will never be known, it’s easy to envisage Tanner and Stroud considering the weather as the aeroplane’s four 2,200hp Wright Cyclones rumbled away in the cold winter air while waiting for their ‘Ts and Ps’ to hit the green. With Scampton’s Meteorological Office reporting showers and scattered cloud between 2,000 and 4,000ft along the route and with visibility sitting somewhere between four to six miles, Tanner chose to fly VFR (visual flight rules) – after all, it was a routine flight the crew had flown several times before. In keeping below the cloud, he would be able to see the ground throughout. And with a low-level cruising speed of 220mph, it would take Over Exposed just 22 minutes to cover the 86 miles between the two bases – not too taxing for a man said to be “one of the most experienced B-29 pilots” around.

With a VFR Flight Plan filed with Air Traffic Control by telephone, at around 1015hrs Tanner pointed 44-61999 down Scampton’s near-6,000ft runway and pushed open the throttles.

As the sleek silver and black machine slipped into the overcast skies of Lincolnshire, nobody suspected that it might never return. Ideally, Over Exposed should have touched down at Burtonwood around 1035hrs… but it didn’t. And while not unusual (the weather wasn’t ideal; perhaps Tanner had decided to fly around it or turned back for home?), concern grew gradually – especially when it was realised no one at either Burtonwood or Scampton had heard from the aeroplane. After an hour, it was apparent that something had happened to 44-61999. With all agencies alerted that an aircraft was unaccounted for, and despite the weather getting worse by the minute, the 16th PRS scrambled another RB-29A out of Scampton to begin a search. Before long, it was reported that burning wreckage could be seen on the high ground at Bleaklow – some 31 miles to the east of Burtonwood. It was just after 1500hrs.

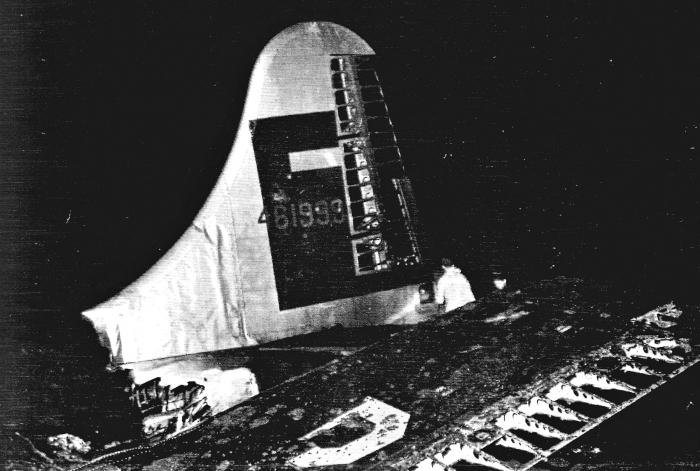

At the time, members of the Harpur Hill RAF Mountain Rescue Team were in the latter stages of an exercise close by when they picked up the messages being broadcast by the searching RB-29A. A Superfortress “was down on the moor and burning”. On hearing the grid reference, the team made its way to Higher Shelf Stones in the hope of finding survivors. But on approaching the blazing wreck through the incessant mist and drizzle it was clear no one had survived. With 44-61999’s tail rearing up from the desolate moor into the darkness – as if already commemorating its lost crew – thoughts quickly turned to recovering the crew and their personal effects. However, by the time night fell, just eight of the 13 had been found, scattered around the still burning remains of what just hours before had been a machine of war.

Grim task

It wasn’t until the next day that the true extent of the crash became apparent. Before dawn, some 50 men tasked with the grim job of recovering the bodies made their way towards Over Exposed’s final resting place from Snake Pass, about a mile to the south. A Harpur Hill serviceman with the surname Allsopp was involved that day. He later recalled: “The Americans were there in force – including a group of Military Police in white helmets, webbing, pistols, the lot. They all appeared to have an unlimited supply of fags, which we took with great alacrity as pay day was due and we had about three woodbines and two dog ends between us!

“The American officer was on the radio most of the time trying to persuade some higher authority that he wanted a fleet of helicopters sending in to fetch the bodies. He kept saying, ‘What f*****g low cloud? Jesus Christ, I can see for miles!’ I gathered that the authority did not think this was correct. We could not see the top of the hill above us. At that time helicopters were a rare sight and not very large at that. He then tried another tack and wanted to know where the nearest US Army heavy construction unit was, to drive a rough road up and across the moor to the crash site to get ‘some goddam f*****g trucks up there and get these poor f*****g guys down, there is no way up there for Jesus Christ’. Well, whether or not Jesus Christ could have got up there I do not know, but our adjutant – Flt Lt E E ‘Buster’ Allen DFC, a former Battle of Britain pilot – was certain we could, and he had us off our backsides each carrying a stretcher, and off we went into the gloom, up the sodden hillside.”

Led by the American officer and armed with torches and arc lamps the group toiled its way across unforgiving, water-logged ravines, stinking peat bogs and streams for two hours before 44-61999’s tail finally loomed out of the gloom of the grey dawn. Allsopp continued: “The walking and stumbling appeared to go on forever in the darkness, you just got to the point of making sure you kept up to the man in front, wondering what lay ahead of us – I had never seen a person that had suffered a violent death.

“About a quarter of a mile from the bulk of the wreck I began to see huge pieces of metal, equipment and papers scattered around – and then I arrived at the rim of the crash site. The rim had been created by the [aeroplane] ploughing into the moor as if it had tried to bury itself to hide the shame of not being able to fly. At the centre were shapes bearing no relation to anything you had ever seen – masses of cable, metal, instruments, seats, equipment of every description, paper everywhere and the bodies of the airmen lying where they had been thrown clear of the aircraft in grotesque positions. There was also a lingering, smouldering smell everywhere – slightly sweet, or was it a sickly smell? It appeared and then was gone, a smell you knew but then you could not place it… like a memory of cooked meat but then it was not. It was elusive but persistent all the time I was there.”

With a search revealing the rest of the crew were still trapped within the tangled, burnt-out fuselage, the recovery party got to work. In doing so, the sheer violence of the crash and fragility of life became evident, as Allsopp noted: “I helped to release a body from the chair it was strapped to – maybe 120ft from the main crash. He had not a mark on his body, apart from a broken neck.”

Finding other bodies, he went on to describe the gruesome scene, adding that it was hard to “put out of your mind that this was a person who a few short hours previously was walking like you and could have spoken to you. He had been a man with hopes, dreams, wife, children…”

Spending hours searching the site, recovering the crew and picking up the likes of wallets, photographs and other personal effects, Allsopp recounted: “You worked automatically, there were things to be moved together, bodies over there, wallets in that box, identity tabs if loose there, watches and jewellery here, so on and so on. We continually went around looking, poking, searching an area again if a body had been there to make sure everything was retrieved for identification and to send back to their next of kin. So it went on until there appeared to be some kind of distorted order and tidiness about the site.” During this recovery operation, someone in the fuselage excitedly shouted: “Look at this!” as he held in one hand a cotton bag featuring the words ‘Wells Fargo’, and clutched a bundle of what appeared to be bank notes in the other: “They were American dollars,” Allsopp recalled. Scrambling toward the commotion, one of the American officers reportedly took the bag, and said: “This is what we’re looking for!” to his colleagues and promptly left the crash site.

“There was $7,400 – it was the payroll for Burtonwood,” said Allsopp, before adding: “Not a note was burnt or even singed, [yet] 13 men had died.”

With all of the crew accounted for, they made their final journey together. Their destination? Burtonwood. As the recovery party made its way down the peak with their grim load, investigators combed the wreckage for any clues as to what had happened. Then a salvage team worked to reduce the wreckage as much as conceivable – a near impossible task given the ferocity of the impact and its location.

What happened?

With the accident committee submitting its report in mid-December 1948, its somewhat indecisive findings noted: “Very little information is available concerning the details of the accident. There were no eyewitnesses to the actual crash. The aircraft was approximately three miles north of course and from all indications was on a heading of approximately 290° magnetic, which is the approximate heading from Scampton to Burtonwood. The time of the crash has been tentatively established from one of the crew member’s watches, which was smashed and stopped at 1050. The aircraft was a total wreck and burned following the impact. There were 13 fatal injuries.”

Since the accident board was unable to definitely establish the cause of the accident, no recommendations were made. That said, some people have noted that findings of USAF air accident investigations of that time appear to be somewhat benevolent when compared with their RAF counterparts.

But how was it that an RB-29A with “one of the most experienced B-29 pilots” at the controls ended up hitting the high ground at Bleaklow? With an ETA at Burtonwood originally logged for around 1035hrs, Over Exposed was still more than 30 miles away (around ten minutes flying time) from the base when it crashed. With no emergency transmissions recorded – suggesting the aeroplane was ‘serviceable’ up until the point of impact – and most agreeing with the committee’s findings, many couldn’t help but express concerns that the loss of 44-61999 was reminiscent of other incidents when a pilot tried to maintain VFR in marginal conditions.

Several theories have materialised. Had a simple navigational or timing error meant the aeroplane was off course? Had the crew taken the opportunity to get in some ‘sightseeing’ around the Peak District before heading back Stateside? Or had the worsening weather forced Tanner and Stroud to look for a way around it to remain VFR?

At the time of the accident, the 311th Air Division’s commanders continually urged their pilots to re-file for IFR (instrument flight rules) if such conditions were encountered. Could it have been that the crew were holding out until the weather passed, or could they have been in the process of filing a new IFR flight plan?

Or did Tanner think he was well clear of the peaks, therefore pushing the aeroplane lower to remain in visual contact with the ground or to establish his position?

Whatever happened on board, 44-61999 ended up on a direct heading with Bleaklow’s Higher Stone Shelf – the second-highest point in Derbyshire. It is doubtful that any of the crew saw the ground before they hit it.

Today, huge amounts of the wreckage – much of it unidentifiable – remain where they fell and a small memorial sits sombrely near to where the 13 crew met hell on high ground.